Huffington Post | December 3, 2010

By Jamsheed K. Choksy and Stephen A. Szrom

Day after day in Tehran, Isfahan, Tabriz, and other cities, the Iranian government exhorts the greatness of the nation’s Shiite Islamic faith. It does so more cautiously in recent months, however, as a revival of Iranian nationalism questions the political legitimacy of mullahs who have controlled the country for over thirty years. As Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad pushes the boundaries of his influence, at the expense of the clerics’, his own appropriation of Iran’s history and pushback from the mullahs have highlighted the continued importance of Iranian civilization’s legacy.

The 1979 revolution replaced a 2,500 year-old tradition of secular, monarchic, reign with a theocracy. Glorifying that imperial tradition, which is rooted in ancient Iranian social and confessional mores, contradicts the bases and the results of the Islamic revolution. For much of its history, Iran was primarily a Zoroastrian (an ancient religion that gave the world notions of good and evil, judgment and retribution, heaven and hell) country. As the Shiite clerics see it, many of Iran’s deep-rooted traditions conflict with Islam’s influence.

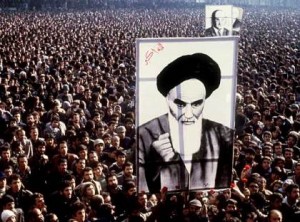

Essentially, both nationalist and clerical ideologies claim descent from two long-standing but separate heritages. Just as Iranian nationalism declares its heritage from Iran’s oldest kings, the clerical establishment claims authority from the prophet Muhammad through a line of imams or religio-social guides. So Iran’s revolutionary leader, the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, argued that since Islam is capable of addressing every facet of life, Iran should be governed by a regime that does not separate faith from state as monarchy did. He established the velayat-e faqih or administration by Shiite jurists that now controls the Iranian polity. Yet, the clerics who seized power have needed to walked a fine line, neither wholly denouncing national pride in ancient accomplishments that many Iranians hold dear nor embracing it and thereby questioning the validity of Islamic statecraft.

Now, given its constant relevance to ordinary Iranians plus its great potential as a tool for political gain, nationalism is beginning to resurge. It is generating a confrontation not just between Iran’s two traditions of state and faith, but between those within the ruling class who champion secularism versus those who still espouse theocracy. Much as Ahmadinejad’s chief of staff, Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei notes, Iran is faced with a choice between the “school of Iran” and the “school of Islam.”