Since the disputed June 12, presidential election in Iran, and the subsequent popular uprising against what has been widely viewed as a rigged election in favor of the incumbent, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the government of the Islamic Republic has been airing its dirty laundry in a way we have never seen before. The cracks in the façade of the regime have been exposed to the world, even as they have continued to grow. Right now, the regime faces its biggest crisis since it consolidated its power in the early 80s.

To understand the current status quo in Iran, and to try to tackle the much harder task of gauging where things may go from here, it is worthwhile to get familiarized with the key power brokers that have been involved in the revolution since the founding of the Islamic Republic.

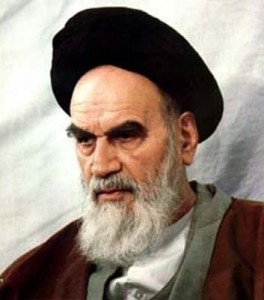

We will start with the figure that most people associate with the founding of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the late, Ayatollah Khomeini. Although he passed away in 1989, the part he played in the revolution still resonates and has tremendous impact to this day.

(Part 1) The Late Ayatollah Khomeini

Born in 1902 in Khomeyn in central Iran, both his father and grandfather were ayatollahs. After attending Islamic schools, he went to live in Qom, a holy city to the south of Tehran. Khomeini was devout and outspoken. He wrote some twenty-one books and many religious articles, often focusing on political issues and how they related to faith. Over time he accumulated a following within the mosque, and in 1962 he became quite vocal in his criticism of the Shah (then leader of Iran). One of his students in Qom was a fellow by the name of Ali Khamenei (not to be confused with Khomeini himself, Khamenei is the current “Supreme Leader of Iran”). Khomeini was arrested and subsequently released, but he continued his criticisms, and in 1964 he was banished from Iran. From 1964 to 1978, he lived in Najaf Iraq, where he continued to agitate against the Shah, growing his following [1]. In early 1970, Khomeini gave a series of lectures in Najaf on Islamic government, later published as a book titled variously Islamic Government or Islamic Government: Authority of the Jurist (Hokumat-e Islami: Velayat-e faqih) [2]. The concept of Velayate Faqih (also spelled Velayete Faghih) later turned out to be a key characteristic of the Islamic Republic of Iran after the 1979 revolution. It means Guardianship of the Jurisprudent, a form of governance where an Islamic Scholar, the Jurisprudent, resides over the decisions of the state. Today’s version of this person is “Ayatollah” Ali Khamenei. More on Ayatollah Khamenei will follow shortly…

The Shah, unhappy with the fact that tapes of recorded speeches by Khomeini were being smuggled into Iran from Iraq, struck a deal with Iraq to have Khomenei deported. The French took Khomeini in, where he established a headquarters at Neauphle le Chateau, near Paris. From there he was able to continue his opposition to the Shah [3]. The revolution was well under way.

Khomeini railed against the Shah, arguing that he was a stooge of the U.S. and Israel. He was against the reforms that the Shah had instigated in what was called the “White Revolution.” The White Revolution was the Shah’s attempt to modernize Iran through various land reforms, electoral changes, the empowerment of women, and a literacy campaign, amongst other things. To varying degrees, the Shah’s reforms were successful. Much of the populace of Iran embraced the changes. However, a key part of the society was staunchly against them. Khomeini was one of the most vocal opponents, representing this group, the Shia Ulema (religious scholars) [4].

Although the 1979 revolution that ousted the Shah was a broad-based movement involving the activity of a large number of groups with converging and diverging interests, Khomeini was able to capitalize on the departure of the Shah by being in the right place at the right time.

A rumour that circulated widely during the euphoria that surrounded the uprising against the Shah, was that Khomeini’s face could be seen in the moon. Many Iranians were enthralled by him.

On February 1, 1979, Khomeini returned to Iran from France, accompanied by various supporters and western media personalities like Peter Jennings. Millions showed up at the airport to welcome him.

On the airplane returning to Iran, Peter Jennings asked him, “What do you feel in returning to Iran?”

Khomeini did not express any elation. His foreboding reply was, “Hichi.” Hichi is the Farsi word for, Nothing.

It was probably at this moment that some in Iran started to question what they were getting themselves into. Iranians are fiercely proud of their 2500 years of history and heritage. Hichi, is simply not acceptable as the feeling that most of them have towards their national and cultural identity.

Little did most Iranians know what Khomeini’s return would herald. A dark era had begun.

(Part 2) Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

Since the June 12, 2009 presidential election, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has been in the spotlight. He currently holds the position of Supreme Leader of Iran, a post he obtained after the death of Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989.

Originally the post of Supreme Leader was supposed to go to a Grand Ayatollah by the name of Ayatollah Ali Montazeri, but Montazeri fell out of favor with Khomeini for voicing criticisms against the execution and torture of thousands of political prisoners.

Khamenei was born to an Azarbaijani father and Yazdi mother, in the city of Mashhad, in 1939. He began his religious studies at an early age. He stayed for a short while in 1957 in Najaf, Iraq, before settling in Qom in 1958 It was there that he studied under Ayatollah Khomeini, amongst other clerics.

Recall that in 1962, Ayatollah Khomeini started to agitate against the Shah. At this time, his Khamenei was twenty-three years old, and he must have been heavily influenced by his fiery mentor. In 1963, he was involved in activities that led to his arrest. He was released shortly afterwards [6].

It must have been in these formative days when he began to develop his radicalism and zeal. Getting arrested by the Shah’s government must have left an impression on him.

Khamenei speaks fluent Farsi and Arabic. He is known to have translated the works of Egyptian Sayyid Qubt from Arabic to Farsi [7]. Sayyid Qubt was an islamist that agitated against the Egyptian government of the time. Another very well-known individual by the name of Ayman Al-Zawahiri was also influenced by the teachings and philosophies of Qubt. Al-Zawahiri, once a member of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, is one number two most important figure in the organization known as Al Qaeda… It is important to note that Al Qaeda has declared Iran a sworn enemy, and the Islamic Republic nearly went to war with Afghanistan when Bin Laden, Al-Zawahiri and Mullah Omar were in control of that country. It is very interesting that they were both influenced by the same individual however.

In 1981, after the assassination of Mohammad-Ali Rajaei, Khamenei was elected president in a “land-slide” vote [8]. From Wikipedia (source):

In his presidential inaugural address Khamenei vowed to eliminate “deviation, liberalism, and American-influenced leftists”. Vigorous opposition to the regime, including nonviolent and violent protest, assassinations, guerrilla activity and insurrections, was answered by state repression and terror in the early 1980s, both before and during Khamenei’s presidency. Thousands of rank-and-file members of insurgent groups were killed, often by revolutionary courts. By 1982, the government announced that the courts would be reined in, although various political groups continued to be repressed by the government in the first half of the 1980s.

Clearly he hasn’t changed his views or methods at all, as is evidenced in the crackdown in the aftermath of the dispute over the June 12, 2009 presidential election.

Also from Wikipedia (source):

Khamenei helped guide the country during the Iraq-Iran War in the 1980s, and developed close ties with the now-powerful Revolutionary Guards. As president, he had a reputation of being deeply interested in the military, budget and administrative details. After the Iraqi army was expelled from Iran in 1982, Khamenei became one of the main opponents of Khomeini’s decision to counter-invade into Iraq, an opinion Khamenei shared with Prime Minister Mir-Hossein Mousavi, with whom he would later conflict during the 2009 Iranian election protests.

From Wikipedia (source):

He served briefly as the Deputy Minister for Defence and as a supervisor of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards. He also went to the battlefield as a representative of the defense commission of the parliament. In June 1981, Khamenei narrowly escaped an assassination attempt when a bomb, concealed in a tape recorder at a press conference, exploded beside him. He was permanently injured, losing the use of his right arm.

In 1989, When Khamenei was selected as the Supreme Leader of Iran by the Assembly of Experts, the post was originally supposed to be temporary. Nevertheless, he has managed to hold onto power for twenty years in this role. He has brought many of the powers of the presidency with him, keeping close relationships with the leaders of the Revolutionary Guards, the military, and key clerics.

His appointment as Supreme Leader is not without controversy. He was not a “Marja” or religious scholar, but he was elevated from the rank of Hojatoleslam to Grand Ayatollah overnight so that he could assume the role. It was a political decision, and was done for the sake of political expediency.

As we have seen since the June 12, 2009 elections and subsequent popular uprising, many of the clerics, including Grand Ayatollahs, disapprove of his policies and actions, and it is not a stretch of the imagination to assume that many of them do not approve of him as a leader at all.

Khamenei is extremely protective of his private life and family. He has given very few interviews. When in one interview in 1982, Elaine Sciolino asked him to describe his childhood and education, Khamenei told her that such questions were a waste of time [5].

In the 1997 presidential elections, Khamenei implicitly endorsed conservative Nateq-Nouri. The state media, and the many resources and organizations at the Supreme Leader’s disposal, all worked to give Nateq-Nouri the upper hand against the other candidates, one of which was reformist candidate Mohammad Khatami (the eventual winner). Khatami won the next election as well, in 2001. His eight-year presidency turned out to be an experiment in how much the regime was willing to bend, to relax and open up, both in terms of contacts with the west, and in terms of loosening some of the social restrictions and persecutions that Iranians have had to endure since the 1979 revolution.

During Khatami’s tenure he challenged the Supreme Leader on numerous occasions, but he was never willing to cross certain lines set by Khamenei. In 1999 a student uprising was put down with brutal force after Khamenei threatened to unleash the Basij if the protests did not stop. Khatami stayed silent as this was happening. His silence was seen as a betrayal by many Iranians who had hoped he would be willing to use his “power of the people” strength to face down the hardliners in the regime (more to come on Khatami soon).

Based on his recent behavior it looks like Khamenei must have internalized a few “lessons” during Khatami’s reign:

- Any concession to the moderates and reformists is a mistake, because no matter what the concession, or how big, they will demand more. The people will become “por ruh” or overconfident and arrogant.

- Concessions to the moderates and reformists are seen by the people as weakness on behalf of the conservatives in the establishment.

- The reformists want to undermine the tenets of the revolution, established by Khomeini and the Islamic Republic party.

- The reformists’ attempts to reach out to the west weakened Iran’s position. They suspended the nuclear program and negotiated with the West for years, only to have the west demand that they halt all nuclear activity completely. Help that was provided by Iran to the Bush administration and NATO during the Afghanistan war and subsequent formation of the new Afghanistan government got Iran nothing in return. Bush even went so far as to label Iran as a member of the “Axis of Evil”. Therefore concessions to the west are harmful to the Islamic Republic.

- The combination of all of these points means the experiment in reform was a mistake, and that a return to the revolutionary ideals on which the Islamic Republic was initially founded is the only way to unify the nation and strengthen it. Any deviation from this path can no longer be tolerated

The Bush administration handed Khamenei and his conservative allies in the clergy and in the security establishment the perfect excuse to start clamping down again, and to start reversing the progress the reformists had made in the society. All liberalizing influences had to be reversed, and if possible, eradicated. The situation was ripe for the return of the conservatives to the executive branch of the presidency, and in 2005, when the reformists had lost credibility with the people (mostly by failing to move Iran even more quickly towards a more open and free society) the opportunity came to the conservatives to use the planned boycott of the elections to bring Ahmadinejad to power (more on Ahmadinejad to follow).

During the first Friday prayer sermon after the June 12 election, Khamenei threw down the gauntlet to the reformists (Mousavi, Khatami, Karoubi, and others) and the pragmatists (mainly Rafsanjani) by basically saying the elections were a done deal, and that the winner was Ahmadinejad. He made it clear that there would be no room for further dissent on this matter, and that any further protests were forbidden. He blamed foreign elements on the protests that had taken place. He made it clear that any bloodshed that might result from further protests would be on the hands of the people that called for them (meaning primarily Mousavi and the reformists). He basically implied that anyone who continued to protest was an enemy of the state.

Considering that by now, there are virtually no credible analysts of the election and the situation in Iran, that think the elections were fair, it is safe to assume that Khamenei ordered the rigging of the election in favor of Ahmadinejad, or at the very least, he turned a blind eye to it.

I have written in another article about the fatwa on his website:

His fatwa reads: “تصميمات و اختيارات ولى فقيه در مواردى كه مربوط به مصالح عمومى اسلام و مسلمين است، در صورت تعارض با اراده و اختيار آحاد مردم، بر اختيارات و تصميمات آحاد امّت مقدّم و حاكم است، و اين توضيح مختصرى درباره ولايت مطلقهاست.” (Taken from the website of the supreme leader [38])

Translation: The decisions and rights of “Vali faqih” (supreme leader) in all the matters that concerns Islam and Muslims, is above the will and decision of the whole nation.

Read that carefully: The decisions and rights of “Vali faqih” (supreme leader) in all the matters that concerns Islam and Muslims, is above the will and decision of the whole nation.

In one fell-swoop he claims that he represents all the matters that concern Islam and Muslims. He then goes on to say that those matters, and his view on them, are above the will and decision of the whole nation of Iran!

You can’t be more clear than that: He (Khamenei) represents ALL of Islam. His decisions in this capacity will be above the will decisions of all of Iran.

And he wonders why people our out in the streets, and why the chant “Allah-o-Akbar!” and “Down with the Dictator!” from their roofs and balconies at night.

Khamenei was involved heavily in the revolution in 1979 that deposed of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. He saw what happened when the Shah backed down and left the country. Combine this with his experience of the Khatami years and his experiment with reform and “liberalization” (if you can call it that even) and his experience during the Bush/Ahmadinejad years where Iran’s power strengthened in the region due to the strategic blunders of Bush, combined with the bellicosity of Ahmadinejad, and you’re left with the following formula:

Khamenei is paranoid about losing his power, and he only seems to understand only fear, terror and intimidation. He believes that his power is derived from these and he uses his instruments of force without abandon to instill fearful submission into the hearts of the Iranian people. Right now he is throwing this power around like there is no tomorrow. Perhaps for him, the only tomorrow that he can fathom is one in which he and his legacy as the representative of Islam and all Muslims on earth reign supreme over the will of the Iranian Nation and its people.

….. TO BE CONTINUED …. Next: (Part 3) Ayatollah Hashemi Rafsanjani

….. STAY TUNED …..

Sources:

[1] Man in the Mirror, Carole Jerome, page 11

[2] Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khomeini, “Life in Exile”

[3] Man in the Mirror, Carole Jerome, page 12

[4] Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khomeini, “White Revolution”

[5] Persian Mirrors, The Elusive Face of Iran, Elaine Sciolino, page 71

[6] Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ali_Khamenei, “Early Life”

[7] Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ali_Khamenei, “Literary Scholarship”

[8] Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ali_Khamenei, “Political Life and Presidency”

Pingback: Iran News - أخبار من أجل الحرية في إيران » Iran’s Power Brokers()